- Home

- Binnie Kirshenbaum

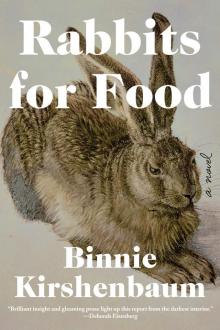

Rabbits for Food Page 7

Rabbits for Food Read online

Page 7

It is counterintuitive to inflict pain, tangible pain, as a way of relieving pain, but pain you can point to, pain that has a place, is pain that can be relieved. Bunny’s pain has no place. She hurts everywhere. She hurts nowhere. Everywhere and nowhere, hers is a ghostly pain, like that of a phantom limb. Where there is nothing, there can be no relief. To bring the pain to a place, like leaves gathered into a pile, to a nexus, no matter how much it hurts, to know that it hurts here, is to bring clarity. Only when she hits herself or pulls her hair or bends her finger back or bites the inside of her mouth can she experience the pleasure of pain found and pain released. It is the only way to be rid of the pain that is Bunny. She is the point of the pain.

Eating Disorders

Having put on his socks and shoes, and therefore now fully dressed, Albie returns to the living room to find Bunny unfurled from her curled-up-in-a-ball position. “Did you sleep?” he asks her.

“I don’t know. What time is it?”

“It’s getting close to one. How about some lunch?”

“Not now. Soon.”

Albie glances at the coffee cup, the second cup of coffee, also untouched. “You didn’t have any breakfast. You’ve got to eat something.”

It’s not an eating disorder like anorexia, and you can forget bulimia, and it’s not like Angela’s stomach cancer, either. People who are clinically depressed have their own disturbances with food. For some, it’s as if hand to mouth were an involuntary reflex, as if food could fill the abyss. Which it can’t, and they grow fat, which does nothing good for their state of mind. The others are rarely hungry or else they are never hungry. They emaciate, become insubstantial, a manifestation of the wish to disappear. Bunny is one of the thin ones.

She was always thin, but now you could rest a teacup on her clavicle.

No, she wasn’t always thin, but she was mostly always thin.

Now, she appears gaunt. Not just undernourished, but malnourished. Her lips are chapped and cracked. Her skin has a gray tint and her hair is flat, lifeless. It could be that she needs a good scrubbing even more than a good meal, but Albie prefers to approach her disturbances one at a time. “I really wish you’d eat something,” he says. “You haven’t had anything since yesterday afternoon.”

“I didn’t have dinner? I thought I’d had dinner.”

“You had a late lunch,” Albie says. “You need to eat. There’s some nice cheese in the refrigerator. A fontina and a Morbier. From Murray’s. And there’s an Amy’s sourdough in the freezer.”

“Really,” Bunny says. “I’m not hungry. But you go ahead.”

“I have a lunch date with Muriel,” Albie tells her. “That is, if you don’t mind my going out for a while.”

The holidays have resulted in an abundance of togetherness, and Albie is desperate to escape, even if only for a few hours. The air is stifling, thick and dank from Bunny’s misery and neglect of her personal hygiene. Her linen—sheets and pillowcase—are squirrel gray with grime.

“I don’t mind. Really, it’s fine,” she assures him.

And it is fine. Even if Albie’s presence didn’t feel like a plastic bag over her head, it would’ve been fine. One example of their compatibility is that neither of them believed that to be married was to be conjoined at the hip. Trust is, and has always been, solid and their loyalty to each other is complete. Trust and loyalty in the ways that matter most.

When Bunny and Muriel met for the first time, Bunny later said to Albie, “You should tell her to lighten up on the mascara.” Then, to put her remark in perspective, Bunny added, “But I really liked her.” About Bunny, Muriel had said, “She’s quite fabulous.” Yet, neither Bunny nor Muriel made any effort toward a friendship of their own because Muriel was Albie’s friend, his friend from work. A friend from work should be a compartmentalized and exclusive friendship; that is, my friend from work, as opposed to our friend from my work. Everyone should be free to go to lunch or dinner with a good friend from work without your significant other sitting there at the table letting go with bull-snort exhales of boredom laced with rising irritation while you and your friend are having what amounts to a private conversation about office intrigue.

Bunny knows that no matter what, you’ve got to have a friend all your own. Albie and Stella got along famously, but Bunny and Stella had a history together, one that was pre-Albie, one that didn’t include him. Stella was Bunny’s friend. Muriel is Albie’s friend, and Bunny is glad he has her.

To hurry him out the door, Bunny tells Albie to have a good time, and Albie asks her, “Do you want me to bring anything back for you?”

“A pack of cigarettes,” Bunny says.

“That’s it?” Albie asks.

That’s it. Bunny doesn’t want anything else except for Albie to go out and to leave her alone. Alone, as if it were something she’d come to regret.

Holding On

The mechanism of a lock turning makes a definitive, finite sound, and Bunny listens for the final reckoning of the tumbler as it falls into place. When she hears the elevator doors as they open and close, sounds less vivid but still audible, Bunny sits up, and pivots so that her feet are on the floor. Something under her skin, but deeper near to bone, throbs like an infection, pulsates the way a heart beats, something that cannot be quieted or contained, but it can, and does, expand. Bunny grabs her pillow, hugs it, squeezing the life out of it, and this, whatever it is that feels like love but is not love, definitely not love, pushes from the inside to get out.

The impact of a plate or a book, when hurled across a room, is declarative, but the pillow proves to be a disappointment similar to the disappointment of a hurricane that changes course and blows out to sea.

Because there are some thoughts, certain kinds of thoughts, that need to be said aloud, Bunny needs to articulate the words to make them tangible and undeniable. Even if no one is listening, the words are there, like a pet rock on your night table, just there, doing nothing, but over time stone does turn to sand, and out loud Bunny says, to no one, not even Jeffrey, “I do not want to be in this world.”

To see her when she stands up is to know that the grimy white T-shirt reaches just below her hipbone. Her black panties sag at her butt. Not that she cares, although she does remember her mother’s admonition about the importance of clean underwear because what if you got hit by a car.

“I’m pretty sure if I were hit by a car,” Bunny had said, “I wouldn’t be thinking about my underwear. I’d be thinking about other things. Like am I going to lose a leg.”

No one need be concerned that Bunny will be wearing dirty panties when she walks in front of a bus because she would never walk in front of a bus, just as she’d never jump from a window or a cliff. Bunny believes, she has always believed, that life, all life, is sacred. You don’t just snuff out a life on a whim. She is a person who apologizes when she kills a bug, despite being well aware of the fat lot of good her apology does for the spider whose guts are squashed on the kitchen wall.

Bunny does not want to kill herself. She does not want to die. It’s that she no longer wants to live. To not want to be alive is not the same thing as wanting to be dead. Bunny would prefer to die of natural causes, but she’s not sure she can wait it out.

Imagine it this way: imagine being on the twelfth floor of a burning building and your options are to be consumed by the fire or jump from the window to a certain death. Can you cling to the hope of being rescued, saved from being burned to a crisp by two brave firemen? Can you bear the intense heat for just a little bit longer? But to feel the heat of the fire, to hear the snap and pop of the flames, to be overcome by the smoke, to be unable to breathe, to imagine melting like wax, melting like the Wicked Witch of the West, and then comes the moment when you know that no one is going to rescue you; when you know that you will either die by fire or jump from the window and die by falling. Neither choice is a good one, bu

t still, you’ll have to decide which way you are going to die, which will hurt most.

A Brief Return to the

Subject of Coffee Mugs

When the Francine mug broke, Bunny tried to gather up the pieces, hoping to glue them together, but there were too many pieces, too many chips and shards; bits the size of motes of dust.

Means of Escape

With Jeffrey trotting alongside her, Bunny walks to the bathroom, where she stops at the threshold. With one hand on either side of the open door, she grips the molding as if to bar exit or entry. Her thoughts, along with her gaze, are fixed on the bathtub. Rectangular shaped, flat to the floor but with early twentieth-century fixtures. White porcelain faucets, Hot and Cold enameled in Dutch-blue script on round caps set into brass findings. The spigot, too, is brass. Solid brass, bought when Bunny had ideas to remodel the bathroom with a freestanding sink and a claw foot bathtub. Soon after buying the faucets and spigot at a boldly overpriced salvage warehouse, Bunny’s attention drifted, redirected, away from remodeling the bathroom. To where or to what is irrelevant. What matters here is her lifelong lack of stick-to-itiveness: oil painting, sewing, piano, guitar, graduate school for applied linguistics, archery, chemistry, refurbishing furniture, or when she was fifteen and signed on for volunteer work at the Simms Home for Mentally Retarded Children, an altruism which lasted less than an hour when she discovered that these mentally retarded children were not preternaturally wise children who happened to speak in simple sentences, but in fact were overweight adolescents who grabbed at her breasts. Whatever she started, Bunny quit.

Except for writing, writing fiction. With that she persevered.

She should have stuck with archery.

All she wanted was to be taken seriously. Was that too much to ask for?

How can you expect anyone to take you seriously when, as one astute critic put it, your book jacket looks like an ad for a feminine hygiene product? The cover that her editor explained was intended to appeal to the widest common denominator.

The widest common denominator is also the lowest common denominator.

How can you expect anyone to take you seriously when you have a child’s name?

Aside from the porcelain faucets and brass spigot, the bathtub itself is nothing special, although it is deeper than the average bathtub, thereby it’s a tub conducive to long, relaxing baths, with bubbles.

Nerve Endings

How could she do this to Albie?

What is difficult, if not impossible, to understand, unless you’re in the thick of it yourself, is that she would not be doing this to him. Albie has no place, not so much as a cameo shot, in this picture, in the video that plays in her head. Pain, fixed with laser beam focus on itself, is self-centered, allowing for thoughts only of alleviation. Even the pain of something as common and comprehensible as a toothache, one of those cavities sufficiently deep to expose the nerve endings, a cavity that feels like someone has jammed an ice pick through your eye, shrinks your world into an impenetrable bubble of agony. It hurts, and it hurts, and that, the hurt, is everything. You can’t think about anything except wanting the hurt to go away.

Ideation

Bunny pictures the bathtub. It’s filled with warm water; a pack of cigarettes and ashtray are on one ledge. On the other ledge of the tub is a wineglass, but it’s filled with vodka, not wine. She will smoke a cigarette and drink the vodka in a measured way. That is, in neither diminutive sips nor swigging it as if she needed it to assuage a particularly bad day or to steady her nerves, as if her hands were shaking. But her hands would not be shaking, and this day would, in fact, be far better than the days preceding it. She’ll smoke the cigarette, and she’ll lean back in the tub and picture an end-of-summer afternoon, late August. She’ll picture floating on an inner tube on a lake, squinting up at the late afternoon sun as the shadows shift and light breaks through the dark density of the fir trees. When the bathwater cools, Bunny will extend her left leg and turn the H faucet with her foot, prehensile in its ability to perform that particular task.

Did it ever happen, Bunny wonders. Was there ever an end-of-summer day when she floated on an inner tube on a lake surrounded by fir trees and squinted up at the sun? Not that it matters. On this last day of December, there is no end-of-summer afternoon, no inner tube, no lake. But still, her ideation is not unlike squinting up at the sun, the way the light breaks through the darkness.

One more cigarette; she’ll smoke that one, too, to its very end. Alongside the ashtray is the box cutter, and not pausing for so much as a thought, she’ll cut one wrist, then the other. Immediately, she’ll wish she’d had one more cigarette, but it will be too late for that. She will watch her life flow from her wrists into the bathwater, and as if blood were food coloring and this, exsanguination, is like a grade school science experiment, the bathwater will turn pink and grow cold, and because she’ll no longer have any control over what is happening, there will be no way for her to stop Jeffrey from pawing at the door, which he always does when Bunny is in the bathroom. He doesn’t like to be left alone. Bunny sees herself well into leaving the world, or maybe she’s already gone, when sweet stupid Jeffrey gets the door open, and instead of drinking from the toilet as he usually does, as if he believes himself to be a lion drinking the cold water from Lake Tanganyika, she pictures him lapping the pink bathwater.

Here is where Bunny’s ideation quits. To picture Jeffrey, having no idea that she’s dead, drinking the bathwater pink from her blood, that just about kills her.

Lunch

A sign, hand-written on cardboard, is taped to the door: We will be closed from 5 p.m. 12/31 and reopen on January 2nd. The Far Left Corner Café—referencing location, not political leanings—is a soup and sandwich place, not a New Year’s Eve hotspot, but now in the afternoon, every table is taken. Albie scans the room looking for Muriel. She is seated in the back at the table next to the bathroom. As he makes his way over to her, Muriel gets up to greet him, tucking a lock of her hair behind one ear. Shoulder-length hair. Thick, glossy, ash-brown going gray at the temples. Muriel is from England, and she looks it, like a woman who has a garden that produces prizewinning gladiolas. She is tall, large-boned, and solid. The Venus de Milo but with arms. She’s an attractive woman, if a touch horsey. Her skin is flawless, white and pink like the inside of a seashell. The only makeup she wears is the mascara that draws attention to the color of her eyes, the light blue of sea glass. Albie takes hold of her hands, strong hands. Almost masculine, but her fingernails are incongruously painted cherry red. Albie and Muriel kiss in greeting. A platonic kiss, although it lasts a beat longer than you might expect from a kiss between friends.

When they break apart, Muriel cocks her head like a bird, a parrot, and in a parrot-like way, a British parrot, she says, “Hello darling.” It’s a joke between them. A private joke, one of those jokes where you really have to be one of the players for it to be the least bit amusing. Only when they are seated does Albie remark on the slight stench wafting from the bathroom, along with the squares of trod-upon toilet paper, which lead like a trail of bread crumbs from the bathroom to just beyond their table. If anything is to be gleaned from this seating arrangement, it’s Muriel’s sense of proportion. As a cultural anthropologist, Muriel has seen children with their hands cut off, famine and disease running rampant, elephants slaughtered for spite, all of which keeps a table by the bathroom in perspective. When she says, “It was the only one available. Can you bear it?” Albie nearly swoons over how reasonable she is, how rational, how not crazy.

“You look good,” he says, to which she says, “You don’t. You look dreadful.”

“Not half as bad as I feel.”

“Do I dare ask?”

All Albie can do is shake his head.

“That bad?” Muriel says.

“Worse,” Albie tells her. They have yet to look at the menu, but the waitress is there at their tabl

e. Her pad open and her pen poised. Albie orders what he had the last time he was here, what he orders every time he is here, an avocado and tomato sandwich on whole wheat toast, extra mayo. Muriel asks about the soup of the day, which turns out to be lentil soup. “My favorite,” Muriel says, as if the waitress played a part in lentil being the soup of the day.

Albie adds two Dr. Brown’s cherry sodas to their order, and then looks to Muriel who nods, and asks the waitress, “Can you put a shot of brandy in those?”

“We don’t serve alcohol here,” the waitress says, and Albie explains that Muriel was joking, and, as if further explanation were required, Albie says, “She’s from England.”

When the waitress is done with them and they are alone, Muriel tells Albie about her visit with her family, about mass on Christmas Eve and mass on Christmas Day at the Anglican church where her father is a bishop. “Then, of course, there was the huge dinner with my brothers and their wives and masses of little ones. It was perfectly lovely,” Muriel says, “and positively stifling. And yours?” she asks.

Prompt: A Hat (300 words or less)

It’s Sunday afternoon. A man and a woman, both in their late sixties, sit side by side on the cafeteria-style chairs. I watch them from a distance of two tables away. The man and the woman are husband and wife. They have been married for over forty years. The chairs are uncomfortable. So are the man and the woman. They don’t want to be here. They live in Queens. They don’t like to come into the city, which is what they call Manhattan, although there is nothing much Manhattan-like about this part of Manhattan. I’d never say that this couple looks younger than they are, because they don’t, but they seem to be from another time, like they’ve been jettisoned from the 1950s or ’60s to now, to the first days of 2009. It could be because of their hats. Despite the fact that it is warm, stuffy even, in this dining room, neither of them has yet to take off their coat or hat. They look as if they don’t plan to stay more than a couple of minutes. The woman has unbuttoned her coat, but the man has not. His coat is the kind often referred to as a car coat, which is something between a traditional coat and a jacket. It’s gray, not 100-percent wool, but a wool blend with pile lining and knit cuffs. His hands are jammed in the pockets and, although I can’t see them, I imagine they are balled into fists. The woman’s coat is her good coat, the one she wears on Sundays and special occasions. It’s navy blue. She got it on sale at Macy’s nine years before. Folded neatly in her pocketbook is her ivory-colored church veil, which is 100-percent polyester. Her pocketbook is on her lap, and she grips the strap with both hands. His hat a Donegal tweed flat cap, brown and beige, with a snap brim. It came from Ireland and cost a pretty penny. The man never would’ve spent that kind of money for a hat, but his brother, who might or might not be into something crooked, bought it for him at least twenty years ago. Although he has never said this to anyone, the man loves the hat and in the winter months, he rarely takes it off. In the summer, he keeps it on the top of his closet in a ziplock bag to prevent the moths from getting at it. The woman’s hat is hand-crocheted, a cross between a beret and a beanie, and the yarn is blue ombré, festooned with a pom-pom on top. She did not crochet the hat herself. She doesn’t have a knack for that sort of thing.

Rabbits for Food

Rabbits for Food