- Home

- Binnie Kirshenbaum

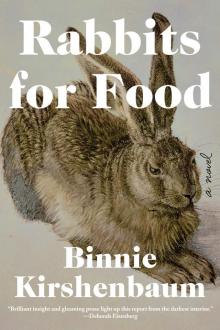

Rabbits for Food

Rabbits for Food Read online

Copyright © 2019 by Binnie Kirshenbaum

All rights reserved.

Published by

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kirshenbaum, Binnie, author.

Rabbits for food / Binnie Kirshenbaum.

ISBN 978-1-64129-053-1

eISBN 978-1-64129-054-8

1. Psychological fiction. I. Title

PS3561.I775 R33 2019 813’.54—dc23 2018059655

Interior design by Janine Agro, Soho Press, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Anthony, Ferne, Isaac, Lucie, Newton, and Susan

Carorum meus, ego te requiro

Part 1

Waiting for the Dog

The dog is late, and I’m wearing pajamas made from the same material as Handi Wipes, which is reason enough for me to wish I were dead. I’m expecting this dog to be a beagle, a beagle dressed in an orange dayglow vest the same as the orange dayglow vests worn by suitcase-sniffing beagles at the airport. To expect that the do-gooder dog will be the same breed of dog wearing the same outfit worn by narco-dogs no doubt reveals the limitations of my imagination.

On the opposite wall from where I sit is the Schedule of Activities board. The board is white, and the Activities are written in black marker across a seven-day grid. Seven days, just in case I want to plan ahead, map out my week. Next to the board is the clock, one of those schoolroom-type clocks, which moves time as if through sludge. That’s it. There’s nothing else to look at other than the blue slipper-socks on my feet. Shoes with laces are Not Allowed. Other shoes Not Allowed are shoes with high heels or even kitten heels, as if a kitten heel could do damage, which is why I’m wearing the blue slipper-socks. Slipper-socks with rubber chevrons on the soles. Chevrons are V-shaped, but the V is upside-down. The slipper-socks also come in dung-colored brown.

A partial list of other things Not Allowed includes: pencils, nail clippers, laptops, cell phones, vitamins, mouthwash, and mascara.

It doesn’t take long to grow bored by my slipper-socks, and I turn my attention back to the clock. The second hand stutters, ffffffifty-one, ffffffifty-two. A watched pot never boils. My mother used to say that, that a watched pot never boils. Also, every cloud has a silver lining, tomorrow is another day, and time heals all wounds. Words of comfort that invariably resulted in a spontaneous combustion of rabid adolescent rage. One of the nurses, the tall one, tall and skinny, gangly not graceful—Ella, her name is Ella—walks by, and then as if she’d forgotten something, she pauses, pivots and retraces her steps. “Mind if I join you?” she asks. To sit on the bench, Ella has to fold herself as if her arms and legs were laundry.

In stark contrast to the rest of her, Ella’s head is round like a ball; bigger than a baseball and smaller than a basketball, but that’s the shape. Exactly like a ball. She’s like a stick figure come to life, having stepped out from that ubiquitous Crayola crayon-on-paper drawing, the one with the three stick figures and a tree and a square house with a triangular roof set like a hat at a jaunty angle. From the upper left-hand corner, a giant yellow sun warms this lopsided two-dimensional world. No doubt it’s some standard developmental thing, that most children draw the same crap picture at the same crap-picture stage of life. Except for the prodigies and the children who are already fucked up. With the fucked-up ones you get a different picture, something along the same lines, but with the house on fire or the stick figures missing their heads. The prodigy, as young as the age of four, will draw a split-level house with gray shingles, and in the foreground, beneath a maple tree in autumn, a dog frolics in a pile of leaves. I know this for a fact because my sister, the older one, Nicole, was a prodigy in art although later she did not live up to her potential, assuming there was potential and her talent was not one of those things kids simply outgrow, the way my younger sister, the third of us three girls, was born with allergies to milk and wool among other things, which she outgrew at puberty.

Ella and I sit here on the bench as if the two of us are in this together, as if we are both waiting for the dog, but then Ella says, “You know what, hon? I don’t think the dog is coming today.” Ella calls everyone “hon.” I’m not special, which is one of the things that about kills me from the hurt of it, that I’m not special.

And worse than the hurt of not being someone special is the shame of it, the shame of how much I want that, to be someone special.

The dog is supposed to be here. It says so on the Activities Board. Mondays and Thursdays from 10 a.m. to noon: Pet Therapy (Dog).

“He didn’t come on Monday, either,” I say, and the sorrow I experience about the dog not showing up is way out of proportion to the fact of it, but that is why I’m here, isn’t it? Because the sorrow I feel about everything is bigger than the thing itself?

At home, Albie and I have a cat who is almost, but not quite, two years old. A rescue. Literally. A man found him in a brown paper bag in a trash can on Third Avenue and Sixty-First Street. A kitten tossed into the garbage as if a kitten were a banana peel. We named him Jeffrey, and on his first day in his new home, he trailed after me the way a duckling follows its mother, or the way a puppy would’ve trotted at my heels. “I know he looks like a cat,” I said, “but I think he might be a dog.”

The following morning after Albie left for work, I got out of bed, as it was my habit to start my day alone. Here, now, in this place, there is no such thing as alone, which would drive me out of my mind, if I weren’t already out of my mind. Jeffrey raced to follow me to the kitchen where I put fresh food in his dish and clean water in his bowl. Down on one knee alongside him, I gave him a scratch behind the ears and kissed him on the top of his soft little head before getting up to take a shower.

It was only after I’d rinsed the shampoo from my hair, when I opened my eyes, that I found Jeffrey there, at my feet, in the shower, looking up at me as if mildly confused: Why are we getting ourselves wet on purpose? I scooped him up into my arms and turned away from the shower spray to cuddle him, to shelter him from the storm raging at my back. In the telling and re-telling of this episode, I would leave out the last part and let the story be about nothing other than a goofy kitten’s extreme cuteness.

Ella suggests that we give up on the dog for now, that I join some other Activity. “So, what do you think, hon? How about Arts and Crafts?”

On Monday when the dog didn’t show up, I went to Arts and Crafts.

Activities are not exactly mandatory but, as Dr. Fitzgerald made clear from the get-go, the road to mental health is paved with Activities such as Painting with Watercolors, Board Games, Origami, Spirituality, Yoga, or even worse—Sing-along, for example.

“Positive interaction within a group is a strong indication of mental health.” Dr. Fitzgerald could not stress enough the importance of social engagement with the other lunatics.

Even at my mental-healthy best, I’m not one for Activities. Positive interaction within a group has never been much part of my social experience. “It’s not just now,” I tried to explain. “Please,” I said. Please, the please subverted an assertion into a request, as if I were asking a favor, as if I were begging.

I do not want to go to Arts and Crafts again. The Arts and Crafts therapist clearly believes that a troubled mind is a simple mind, that to be clinically depressed is the same thing as to be a congenital idiot. In Arts and Crafts on Monday, we glued mosaic tiles to a square piece of wood to make the exact same whatever-the-fuck-it-was that I made in arts and crafts class in

the third grade. Even in the third grade, I knew that this was something only a demented person would want, and sure enough, the obese loon sitting next to me asked if she could have mine. That night after dinner, when Albie came to visit, I told him, “I made something for you in Arts and Crafts, but one of the crazy people stole it.”

As if perhaps there is something she’s overlooked, Ella concentrates on the Activities Board. She has overlooked nothing. She knows what choices remain: Creative Writing or Jigsaw Puzzles.

Granted, I am clinically depressed but I’m not that depressed, so low as to go with Jigsaw Puzzles, and Creative Writing—you’ve got to be kidding me.

Prompt: An Introduction (300 words or less)

Bunny

Funny Bunny

Bugs Bunny

Bunny Wabbit

Honey Bunny

Easter Bunny

Fucks like a Bunny

Bunny Bunny Punkinhead

Voyage to the Bunny Planet

Playboy Bunny

Ski Bunny

Beach Bunny

Dumb Bunny

Dust Bunny

Energizer Bunny

Echo and the Bunnymen

Bunny Lake is Missing

Bunny Hop

Fluff Bunny

Bunny

Where to Begin

December 31, 2008. All too often paper hats are involved. Other things about New Year’s Eve that mortify Bunny are false gaiety, mandatory fun and that song, the one that’s like the summer camp song. Not “Kumbaya,” but that other summer camp song, the secular one, where everyone links arms and they sway as they sing, “Friends, friends, friends, we will always be.” It’s not that song either, but the New Year’s Eve song also requires arm linking and swaying and it sentimentalizes friendship with an excessive sweetness that is something like the grotesquerie of baby chicks dyed pink for Easter. The overplayed enthusiasm for the passing of time, the hooting and hugging at the stroke of midnight baffles her, as does the spastic rejoicing to be that much closer to old or dead, as if old or dead were something to be won, like a three-legged race or American Idol. The only way Bunny knows to keep safe from the countdown New Year’s Eve is to lock herself in the bathroom and wait for the fanfare to fizzle out like the silvery sparks of a Catherine wheel.

But there is time yet.

It’s still morning, and although her eyes are closed they might as well be open, the way she knows Albie is there at the foot of the couch, looking down at her, just as she knows that he is wearing blue jeans, a pair faded from wear—never pre–faded or stone-washed or anything but 505 Levi’s—and a light blue button-down oxford shirt, one of the same Brooks Brothers button-down oxford shirts he’s been wearing since he turned twelve. For thirty-three years he’s been wearing the same make and style shirt, although there has been variation in the color. That is, if you consider white to be a color. On his feet are rubber beach slippers. Not flip-flops, but rubber slippers with two wide straps that crisscross; rubber slippers that are generally worn at the beach by skinny old men in plaid swim trunks whose perfectly round bellies protrude as if they’d swallowed a honeydew melon whole, the way a snake swallows a rodent whole, and you can see, all too clearly, the shape of the mouse until it is digested. When a python swallows an alligator or a person, such as that fourteen-year-old boy in Indonesia, the shape of the meal is sharply defined for days or weeks. This is one of those things she wouldn’t have minded not knowing, and it’s not an easy thing to forget. Even now, when there is much that she forgets, she remembers that if an anaconda eats your dog, the outline of your dog will be visible for far too long. Although Albie’s belly does not protrude like a honeydew melon, he has developed a hint of a paunch, just a hint but, coupled with the rubber slippers, it is enough to distress her. Then again, what doesn’t distress her? Well aware that when she opens her eyes, she will find him dressed exactly as predicted, and for the duration of a flashbulb popping, she will hate him for his predictability, and for the forlorn irrevocability that accompanies a solid marriage, a marriage that requires no effort, which is meaningful disappointment only if you stop to give it some real thought, if you stop to give it, like the rubber slippers, more attention than it deserves.

“I’m awake,” Bunny says.

To sit beside her, Albie needs to sidestep one of the five or six stacks of books on the floor. Books stacked without a plan, just as the books in the floor-to-ceiling bookshelves are arranged carelessly. His books. Her books. The books she reads, as opposed to her books, as in books she has written. Those, the many remaindered copies of them, are in boxes and, like all bogeymen, they are hidden under the bed.

Albie doesn’t write books. He publishes articles and papers in magazines like the Journal of Natural History and Animal Ecology but, for him, public recognition has no bearing on the pleasure he derives from his work. He is freakishly well-adjusted. The books that are his, those he reads, are an eclectic and, unless you know Albie, an irrational lot. Aside from zoology and its related fields, his interests include cartography, game theory, philatelic history, ancient Greek poetry, and magic tricks, among other super-nerd subject matter, although—the rubber slippers excepted—Albie is not a super-nerd person. Not even when he was a teenager, but that could be because he went to Stuyvesant High School where geeky boys are considered dreamy.

Bunny’s range of interests is also varied: history, politics, antiques, animal rights, psychology, fashion, and literature, serious literature, although now she is interested in nothing.

Seating himself on the edge of the couch parallel to her hip, Albie keeps some inches of distance between them, the way you’d keep a few inches back from the edge of a cliff, and he asks, “Did you get any sleep?”

Sleep has never come easily to her, but until recently the drugs worked well enough. But now, two or even three times the prescribed dose brings her no closer to drifting off at night like a normal person. Often, she doesn’t fall asleep until dawn, and from there, she’ll sleep away the day, the entire day. You’d think that ten, twelve, thirteen hours of sleep would be restorative, but hers is sleep that keeps to the surface, as if she were floating on a rubber raft in a pool. However relaxing that might sound, to sleep, to really sleep, is not to float on the surface, but to be deep down near the ocean’s floor.

On other nights, nights like last night, when she does manage to fall asleep before the sun comes up, the sleep is fragmented, interrupted by spates of waking and restlessness. It was the waking, the restlessness, and weeping in distress that had cut into Albie’s sleep, too. Despite that weeping wants an audience, it was never her intention to wake him. To cry when no one can hear you could well belong in the category Bunny calls “Wow Thoughts for Stupid People,” like the sound of one hand clapping. But unintentional or not, there came a night when Albie woke yet again to the ugly noises of his wife’s despair, and he snapped, “Shut up. Will you please just shut the hell up,” at which point Bunny took her pillow and went to sleep, or went to try to sleep, on the couch where a few hours later she put the same pillow over her face to block out the relentless morning sunlight. There she stayed until late afternoon when the sun was less aggressive. On her way to the bathroom, she cut through the kitchen where she found a pot of coffee kept warm but gone stale, and a blueberry muffin from Carol Anne’s, her favorite bakery, on a plate next to a note that wasn’t really a note. It was a lopsided heart and xoxo Albie scribbled on a torn-off corner of a brown paper bag. She wasn’t hungry, but because it was there and because Albie meant well, she broke off a piece of the muffin. In her mouth it tasted like an apple going bad, without flavor and mealy.

What Time Is It

Bunny sits up, but not up up. Her feet are not on the floor, but her back is resting against the arm of the couch, which is camel-backed, olive green velvet. What had passed for shabby chic at the time of purchase is now the f

urniture equivalent of a dog with mange. The upholstery is shredded, puffs of stuffing stick out like Albert Einstein’s hair. When Jeffrey had commandeered the couch as his scratching post, neither Albie nor Bunny had it in them to chastise the little idiot for what he couldn’t possibly understand. Also, Bunny’s been occupying much of her time pulling at the fabric’s loose threads. Her legs are stretched out and covered by the blanket as if they were useless, and she says, “Some. I slept some.”

It’s been over a week since Bunny last showered or changed the T-shirt she is wearing, which reeks of sweat and fear and emits a vapor which Bunny pictures as a visible fume of noxious gas, like the way a bad smell is depicted in cartoons. But her unpleasant odor is not why Albie chooses to sit more or less parallel to her hip with the three or four inches of couch cushion between them. It’s because sometimes when he touches her, even accidentally, she flinches. It’s not him in particular. She’d flinch no matter who touched her, but Albie is the only one with opportunity. It’s been many weeks, maybe months since she’s seen anyone other than Albie. And Jeffrey. Because it’s incomprehensible to their goofy cat that a snuggle might not be welcome, he jumps onto the couch where he winds his way into the unoccupied inches of space between Albie and Bunny, as if that space were there purposefully, intended for him. Albie strokes the cat’s ears and asks, “How much is some?”

“I don’t know,” Bunny says. “What time is it now?”

Albie checks his watch. “It’s nine twenty-one.” He cannot help but to be exact. Bunny, however, is an approximator. Piecing together the segments, the snippets of sleep, she calculates, “Four hours. Give or take,” she says.

Albie leans in closer to his wife seeming like he is going to lift a few stray strands of hair away from her face, except he’s about to do no such thing. “About tonight,” he says. “You know we can cancel. It’s no big deal.”

Rabbits for Food

Rabbits for Food