- Home

- Binnie Kirshenbaum

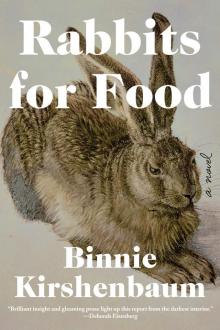

Rabbits for Food Page 6

Rabbits for Food Read online

Page 6

As far as Bunny is concerned, at least in theory, family amounts to no more than shared DNA; as random and meaningless as the collision of two electrons before they are off again, each in its own orbit. Albie and Jeffrey are the whole of her family. Stella had been family, too, like a sister to Bunny except that the filial devotion, the love, was genuine and not foisted upon them by indiscriminate protoplasmic whimsy. Bunny misses Stella. So much, she misses Stella. Some people might say it’s too much, which is like saying that there is too much water in the ocean. The way she misses Stella is different from the way she misses Angela, but it’s the same insofar as that there is no consolation to be had. The loss of Angela and Stella both, feels to Bunny like longing that is endless. But it’s not endless. It’s longing that is limitless.

Bunny’s sisters call because, they say, they are concerned about her. Perhaps there’s something to that, but the real reason they call is for an answer to the question: How did this happen? Have they found the cause? Dawn wants it to be something like food poisoning. She wants Albie to say, “It was the mayonnaise,” although really any explanation will suffice provided it rules out the possibility of the hereditary factor. She needs to be reassured that it’s not one of those genetic mutations that can cause breast cancer or bad teeth. “So it’s definitely not genetic, right?” Dawn has asked Albie this question more than once.

Although it was never Albie’s intention to provoke hysteria in Dawn, he answered her question as best he could, which was to say, “I’m not an expert on these things.”

“Maybe, but still,” Dawn said, “you know more than I do.”

Dawn is desperate for certainty, and she seeks comfort in the fact that her children bear no physical resemblance to Bunny. If they don’t have her eyes or her mouth, then it’s not likely that they got her sick-o gene, either. Right? “Right?” she asked Albie. “They probably don’t have any of her genes. They don’t look anything like my side of the family. You’ve seen them. They look just like Michael. So even if it is genetic, they wouldn’t have that gene, right?”

“I can’t answer that,” Albie said. “I really don’t know.”

Dawn might be a wishful thinker, but Nicole has managed to believe that there’s direct causal link between Bunny’s crack-up and her use of aerosol deodorant. If Bunny’s meltdown can be attributed to her lifestyle—face it, she smokes—Nicole can rest easy. Twice-daily meditation, a raw food diet and a weekly colon cleanse is practically a guarantee that she will not die, that she will never die. However, Nicole can’t quite rid herself of the lingering concern that it might’ve been the bits of Bac-Os that did this to Bunny, the Bac-Os that their mother sprinkled liberally on salads and baked potatoes when the girls were in their formative years.

Nicole’s fixation on a squeaky-clean colon interests Bunny, in a general interest sort of way, a curiosity to occasionally ponder the way she’ll occasionally ponder who killed JonBenét Ramsey.

It’s not only her sisters who ask, “What happened?” People who barely know Bunny from Bonnie, they too want an explanation, a reason they can identify, identify and thereby avoid as if it were a matter of using a condom, or something they can control the way they can control their intake of salt. They want to know what it takes to keep a tight lid on your mind. They say, “We never saw this coming.” If no one saw this coming, it was because no one was paying attention; a lack of attention that might well have been a contributing factor. A contributing factor. One. One of many. Because it’s never just one thing. Still, they ask, “How did this happen?” Because they need to be sure that people don’t fall apart without a solid reason, they sift through her life panning for gold: she spends too much time alone; she’s got a negative attitude; she never had children; she smokes cigarettes; not having children messes with a woman’s hormones; all day working alone, that can’t be good; she eats processed food; she is a middle child; she’s never even been to a gym; she’s not very likable; she’s always been moody, difficult, dark, overly sensitive and easy to anger; even as a child, she wasn’t likable; she should’ve had children; she wears perfume; she drinks too much coffee; she smokes cigarettes.

Whatever the reason, they want to be assured that it was her own damn fault.

Predicting Snow

With an acute dog-type of sensitivity to tone, Bunny detects the catch in Albie’s throat when he says to whomever is on the phone, “Not at the moment.” The catch gives way to artificial buoyancy. “She’s right here. Hold on. I’ll ask her.”

“It’s Trudy.” Albie covers the mouthpiece with his hand. “She wants to know about tonight.”

It’s like a muscle contraction, the way Bunny pulls in on herself, tight, like a pair of pursed lips. She is intent on control, on refraining from the desperate need to hurl the coffee mug across the room or to bite off a hunk of her pillow. When the flash of rage has passed, she asks, as if she did not know, “What about tonight?”

“If we’re still on. She wants to know what our plans are. Because, you know, we’re not sure.”

“Yes, we are sure,” Bunny says. “We’ll be there.”

Again, with the calculated and calibrated enthusiasm of a pep squad captain, Albie tells Trudy, “We’re on. We will see you at eight.” Then, after a pause, he says. “I have no idea.” He returns the phone to the cradle, taking care that it is perfectly aligned the way you would take care when hanging a painting on the wall, and Bunny asks, “No idea about what?”

“Oh.” The word come out like a gulp. “If it’s going to snow.” Albie knows that he’s a lousy liar—he has little experience with the art of prevarication—but he forges on. “Because they’re predicting snow, and Trudy asked what I thought. If it was going to snow or not.”

Bunny pulls at the blanket, wrapping it tighter around her shoulders, and she asks, “What is it you think I am going to do?”

Albie doesn’t respond, which is the worst answer possible. Bunny rolls over, facing the back of the couch, and as if the sky were falling, she presses her hands flat to the top of her head, tucks her chin, and brings her knees to her chest. What’s that animal, the one that curls up into a ball? Jeffrey also repositions himself, cozies into the nest made by the curve of her legs. She wishes she could bring herself to push him off the couch, kick him away from her as if that stupid, sweet cat were an empty soda can.

The Shattering Clarity of the

Irreplaceable, Yet Again

The day before the momentous Election Day of 2008, in that lull of time when it’s no longer afternoon but not yet evening, the sky was washed in opaque indigo blue and, standing at the living room window, Bunny was overcome by an emotion she could not identify. Whatever it was, she thought she might drown in it. She put the palm of her hand, her left hand, flat against the cold glass. An early arctic chill was blowing in from Canada, and just like that, Bunny got inspired. Ice-skating, to go ice-skating, to have fun.

Fun not shared is not fun. You can derive great pleasure alone, enjoy yourself enormously, experience bliss, but fun requires someone else, like a friend or a dog. Jeffrey is not a dog, and Stella is gone.

When she called Lydia, to ask if Lydia wanted to go ice-skating, the phone went straight to voicemail, but Trudy picked up her phone on the third ring.

“Ice-skate?” Trudy asked. “Since when do you ice-skate?”

“I don’t,” Bunny said. “But I did once. I mean, one time.”

At that age, nine or ten years old, girls had ice-skating parties, bowling parties, or played twelve holes of miniature golf; activities followed by a hot dog, a Coke, and a slice of Carvel ice cream cake. At one of the bowling parties, Bunny bowled a zero. She pretended to do it on purpose. Better the girls on her team be mad at her for deliberately failing than for all the girls to goof on her for being a spaz.

In the days leading up to the skating party, Bunny imagined gleaming white skates with pom-poms dangling fr

om the aglets of the laces like a pair of fuzzy dice from the rearview mirror of a car. But the rental skates were the same shade of white as pee-stained sheets. There were no pom-poms, and when she stood up, her ankles turned inward, as if to kiss each other on the nose. While everyone else whizzed past her like they were Hans Brinker and his sisters, Bunny clung to the rail, inching her way around the rinky-dink rink. When she dared to let go, she fell. A fish out of water, Bunny on ice.

“It’s not about ice-skating ice-skating,” she told Trudy. “It’s about falling down.” Bunny effused on the fun of foolishness, the fun to be had flopping and falling on the ice at Rockefeller Center. Her voice sounded as if her eyes were glittering.

“Hardly my idea of a good time,” Trudy said. “And at Rockefeller Center, no less? Where do you get such ideas?” Rockefeller Center is for tourists and adolescents who over-identify with Holden Caulfield. Moreover, there was a documentary about Stockhausen on at seven that she really wanted to see.

“Who?” Bunny asked.

“Stockhausen,” Trudy said. “Karlheinz Stockhausen.”

“Right. Right. Stockhausen.”

To replace lost love, the way you can replace your broken computer with a new one or replace the battery in your watch, is not an option.

Bunny hung up the phone and googled “Karlheinz Stockhausen,” whom, she learned, was a pioneer in aleatory music. Then she googled “aleatory music,” and after that she sat there staring at the computer screen as late afternoon turned into night.

When Albie got home, he wanted to know why was she sitting there in the dark staring at the computer screen.

“For fun,” she said. “I’m having fun,” and then she said nothing.

Bunny doesn’t talk about Stella.

Prompt: An Imaginary World (300 words or less)

The same way Miracle on 34th Street was a movie with an ending that promised disillusionment and a future of amorphic discontent, The Wizard of Oz was another movie from which I could find no hope to salvage. For eighth-grade English class, I wrote an end-of-term paper comparing the film version of The Wizard of Oz to the book version of The Diary of Anne Frank, positing that although the stories and their circumstances were entirely different, both were tragedies born of a pitiably naïve optimism which afflicted both protagonists.

After years of hiding from the Nazis in an attic where there was no such thing as privacy, although there was plenty of stress and raw nerves, along with the fear of knowing perfectly well what would happen if they were discovered, Anne Frank wrote in her diary that, in spite of everything, she still believed that people were truly good at heart; this from the girl whose doom was sealed behind the closed door of a cattle car, whose mortal remains were turned to ash in the incinerator that was Auschwitz* because—yoo-hoo, Anne, get real—what about the people who, in spite of everything, are, at heart, truly sociopathic?

And Dorothy? Liberator of the Munchkins? Rightful owner of the ruby slippers? The darling of the Emerald City? What did she have to say for herself? There’s no place like home. Dorothy wanted to go home. Home, as if home carried with it the implications and assumptions of a place where you are loved and cared for and kept safe; where you have a family, all of whom wear reindeer sweaters during the holiday season because home is a place where it snows in winter and winter is followed by the green of spring as opposed to some miserable scrap of hardscrabble earth where dyspeptic Miss Gulch snatched your dog, bent on snuffing out his little life, all the while Auntie fucking Em just stood there with her thumb up her ass. That was home, Dorothy. And yet, three times she clicked the heels of the ruby slippers as, three times, she said, “There’s no place like home,” which was the magic spell to transport her from the Emerald City to the dustbowl that was Kansas, where dreams shrivel and die like the crops, where Toto would be thrown to the wolves, where the rest of Dorothy’s days would be bleak and lonely because—oh, poor naïve dum-dum Dorothy—“There’s no place like home.”

Under the big red F, which was circled three times, my teacher wrote, “There is something very wrong with you.”

*For the record, Anne Frank did not die in the gas chambers at Auschwitz. She died from typhus at Bergen-Belsen where her body was tossed into a mass grave and buried like toxic waste. And she died six weeks, not two weeks, before the camp was liberated.

But Auschwitz and the gas chamber and the irony generated by two weeks rather than six, make for a better story.

Except it wasn’t a story.

The Point is the Pain

“So, it is okay with you,” Albie asks, “if we skip it?”

“If we skip what?”

A deep breath, Albie sucks back his aggravation. “The party,” he says. “The Frankenhoffs’ party. I really don’t want to go.”

To which Bunny responds, “The windows are hermetically sealed.”

“What windows? What are you talking about?”

“The Frankenhoffs’ windows don’t open. So if you’re thinking I might jump, don’t worry. It’s not possible.”

“Jesus. No. Cut it out, Bunny. Not even as a joke. But really, what is the point of going? To come home and complain about having been bored out of our minds?”

“We don’t have to decide this minute, do we?” Bunny asks.

“No. Of course not. We’ll wait and see. We’ll see how we feel. Later.”

As far as taking a header out the Frankenhoffs’ window, which would be less like a swan dive and more like the Flying Nun, limbs going gawky every which way until the sails of her wimple that looked like folded tablecloth would catch the winds like a kite, even if the Frankenhoffs’ windows did open, it would never happen. People are not kites. With people, gravity kicks in, and Bunny has no calling to splat onto the sidewalk on New Year’s Eve as the ball drops at Times Square.

Never would she make such a spectacle of herself.

Never would she give some fraud at the Frankenhoffs’ party cause to say, “Frankly, I’m not surprised. Did you know that her parents named her Bunny because they raised rabbits? For food.”

Taking note that Bunny has not touched her coffee, that it must be cold by now, Albie asks, “Do you want a fresh cup?”

“What did you say?” She blinks her eyes as if she were just waking up, and not quite sure of her surroundings. “Did you ask me a question?”

Albie repeats his offer to make her a fresh cup of coffee, and Bunny says, “Yes. Thank you.”

“No problem.” He kisses her forehead and then leaves, taking the St. Thomas coffee cup with him.

To fling herself out a window, whether it be the Frankenhoffs’ window or any window, is not Bunny’s idea of the way to relieve what is killing her. Falling or jumping from up high is not of her ideation. Ideation is the way we imagine doing away with ourselves. Even people who would never, ever, kill themselves, they too, although less frequently, indulge in suicidal ideation, imagine their own funerals, relishing the grief, the guilt, the remorse resultant from their self-inflicted death. Ideation, when we get into the specifics of it, when we get down into orchestrated details, is as particular to the individual as are their sexual predilections.

In the kitchen, Albie pours the cold coffee down the sink and drops the mug in the trash, where it lands sailboat-side up. After filling the pot with water, Albie calls out asking if Bunny would like something to eat.

“Not now,” Bunny says.

“I can’t hear you.” Albie raises his voice, “What did you say?”

The pressure of irrationality rises up in Bunny the way atmospheric pressure rises, and under the cover of the blanket, she wraps her right hand around the middle finger of her left hand. It’s similar to warm-up exercises for the piano or the attempt to alleviate writer’s cramp, the way Bunny bends her middle finger back toward her wrist. Because, anatomically speaking, a finger doesn’t bend backward of its own

accord, Bunny ought to be showing signs of discomfort, some indication that she’s gone beyond the point of stretching and nearer to the point of tearing a ligament, but to look at her face you’d think, “Here is someone who is at peace with herself.”

It’s plain white, the cup Albie sets down on the coffee table. Bunny thanks him for the coffee, as if coffee were exactly what she’d wanted, and wasn’t he sweet to know. “It smells good,” she says, acting; acting like a normal person, but she makes no move toward the cup, and a normal person wouldn’t be trying her best to snap off her own finger. Because this particular self-inflicted Torquemadian punishment draws no attention to itself—no howling or wild gesticulations or limbs flailing—and her hands are hidden from view, Bunny is like a junkie shooting up between her toes or one of those teenage girls who cuts herself where no one will see, which was something Bunny never understood. Why bother cutting yourself if not for the attention? But Bunny has newfound insight into these girls. She gets it now, how the release of the pressure, like air escaping from a balloon, can defuse what would otherwise explode.

Albie, again, sits on the edge of the couch, alongside her, and puts his hands over hers, her hands covered by the blanket, and gently pries them apart.

More than the weeping, more than the lethargy, more than the utter battiness of it all, it’s the self-inflicted trauma that disturbs Albie most.

Her thighs are a bleed of bruises, like a pansy, purple- and yellow-tinged with the green of the sky before a storm. Whenever she pummels herself or smacks her head, hard, with the palm of her hand, Jeffrey flees to a safe spot under the bed, and Albie wraps his arms around her as if his arms were a straitjacket, and in that same way, she struggles to break free of him. To be held tight like that is suffocating, and she gulps for air. These episodes cross the line of that with which he can cope, and that which is simply too damn much for him. “Please,” he says. “Please don’t hurt yourself.”

Rabbits for Food

Rabbits for Food